Suzanne MacLeod | September 2024 |

How might museums utilise research and strategies from fields such as implementation science to drive evidence-based decision making, understand which changes in museums successfully broaden visitor demographics and sustain progress towards representative participation? Could Implementation Science help us to identify a new area of museum practice focused on closing the attendance and benefit gap and new ways of utilising museums’ research resources to these ends?

Context

The Addressing the Museum Attendance and Benefit Gap Network has been working together for well over a year now to understand the implications of population level data. The data tells us that despite significant audience-centred developments in museums, a vast array of best practice guidelines developed in Museum Studies and the overall growth in the number of visitors to UK museums, the sector is characterised by deep and persistent inequalities in museum attendance and benefit. The attendance and benefit gap (the gap in attendance and benefit between highly educated and economically advantaged people and economically disadvantaged people with less formal qualifications) remains unchanged at circa 24 percentage points and museum audiences continue to be defined by higher educational achievement and higher levels of economic advantage. Put another way, the majority of UK museum audiences do not reflect local demographics, despite most museums claiming inclusion as a key strategic aim. It is very clear that museums are lacking a systematic approach to closing the attendance and benefit gap. This situation is compounded by museums’ current uses of research resources. Our key concerns as a group then, are to:

- understand what we already know (what evidence do we have of changes in museums that lead to a broadening of museum audiences?);

- generate methods, processes and uses of research which will enable us to specify which changes in museums lead to a broadening of museum audiences, are replicable in different contexts and scalable across the sector;

- identify what museums of different scales and types need to do and how they might need to change in order to implement what is known in order to optimize benefits and outcomes for a much broader section of society.

A focus on Implementation Science

This blog is a reflection on our 4th Network Workshop where we focused on Implementation Science – an area of health research which, as one of our guest speakers described, aims to ‘sustain implementation of the best innovations everywhere to optimise outcomes for all people’. Recognised as a ‘catalyst for health system reform’, Implementation Science brings grounded theories, frameworks and models to support researchers and practitioners to get evidence-based findings and solutions into routine practice – it focuses on ‘developing and testing methods to broadly spread successful sustained implementations across diverse settings’ (Damschroder 2019). Key here are frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a framework to support implementation in complex settings.

In the Network, we are interested in what it might mean to generate a field of Implementation Science in museums that is evidence-led and which could, if approached in a systematic way, be scalable. Put simply, focusing on implementation in a sector that struggles – in both museums and in museum studies – to evidence the causes of changes in who visits, where there is lack of clarity about the strategies most likely to achieve this and where research is often non-generalizable, focused on evaluating impact on small groups of people – seems to offer a productive way forward. If we could generate a science of implementation in museums, we may well be able to create ways of thinking and talking, approaches and frameworks that would demand new ways of working but which could build up shared methods and processes for bringing data and evidence to bear on decision-making – helping museum leaders to make decisions about, for example, exhibition content and delivery that are evidence-led – and, through the data that they collect, gradually build up a solid, causal understanding of what works to close the attendance and benefit gap.

There were a number of initial observations that suggested Implementation Science could help.

In relation to our research puzzle – how might we close the entrenched and persistent museum attendance and benefit gap – Implementation Science holds potential as it concentrates on getting research knowledge and evidence into practice – its aim is to close the gap between research and practice. We know that there is a gap between the large data that tells us that the attendance and benefit gap remains and may even be growing and that this is complicated by the vast differences in research in Museum Studies, Cultural Sociology and museums themselves. Closing these gaps and providing clarity about what we know and want to bring to bear on the cultures and making of museums in order to close the attendance and benefit gap, is crucial. It demands that we understand what research and evidence we have to work from.

Related to this is a second area where Implementation Science seems especially rich – museum practice. Museums do not currently talk about implementation or identify implementation as a separate category of work. In terms of evaluation, emphasis is usually placed on evaluating whether the anticipated outcomes for participants have been achieved. Implementation Science insists that that we deepen our focus and become much more precise. It asks that we focus on and identify the difference between the innovation (the new approach that seeks to broaden audiences) and its implementation (how the new approach is operationalised), that we specify both in great detail and that we also prioritise evaluation of the implementation strategies – did we complete all of the strategies identified and to the standard specified? Significantly, Implementation Science is interested in locating causality – which specific innovations that we made and actions that we took resulted in a broadening of audiences? In this sense, Implementation Science puts the emphasis on the deliverers of the innovation (e.g., museum staff), which again seems attractive. What changes to museums effectively closed the gap and how can we sustain them? Whilst the in-depth focus on implementation that Implementation Science brings does feel new for museums, it also chimes with and could be understood as a deepening of recent work in a number of museums to introduce Theories of Change into their work.

Finally, in terms of our larger research project and process, whilst there are some complexities that we need to work through, Implementation Science seems to be highly compatible with Action Research, the research approach utilised in varying ways by RCMG (the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries at the University of Leicester) and in an ongoing way in museums committed to organisational learning. Based in action, supported by sophisticated frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to both enable and simplify complexity and focused solely on drawing evidence-based practices into complex settings and utilising research resources to ‘sustain implementation of the best innovations everywhere to optimise outcomes for all people’, Implementation Science seems to offer ways of working and approaches that could be built into and enrich an Action Research approach.

Two days of expert input

At the end of June 2024, the Network members were joined in Leicester by Laura Damschroder and Caitlin Reardon – experts in Implementation Science and in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). We had identified Laura and Caitlin’s work as of particular interest to the Network during the process of generating our Network funding application and although RCMG researchers had remained in dialogue with them since and undertaken a good amount of research into Implementation Science in preparation for their visit, the Workshop marked a key moment where we would work to deepen understanding and discussion of Implementation Science amongst all Network members. You can see some of the Workshop content here.

Over two days Laura and Caitlin walked the group through the basic premise and principles of Implementation Science and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). On Day Two of the workshop, we worked in multi-disciplinary, cross-sector groups under the expert tuition of Laura and Caitlin, and began to use the CFIR in relation to specific projects we were currently engaged in.

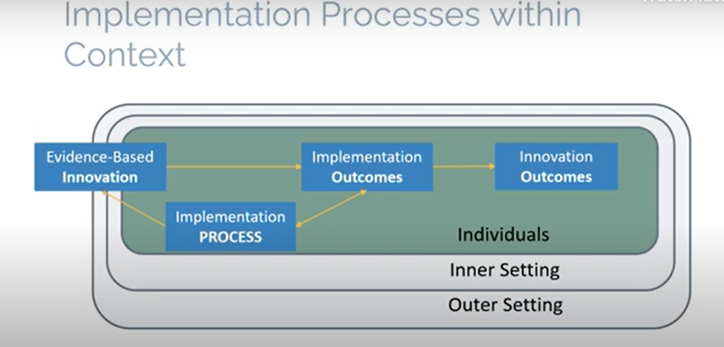

First of all, Laura and Caitlin introduced Implementation Science. They explained that we have to be clear about the theories underpinning our work and how we think we are driving change. We might be right and equally we might be wrong and learn from failure. Laura set out the meta theory or ‘pathway’ guiding Implementation Science [Figure 1] which theorises that implementation takes place in a context and each stage of the implementation pathway is embedded in, interacting with and influenced by these contextual domains – the individual, inner and outer settings. Once you have an innovation that is tried and tested, you enter the implementation pathway which involves ensuring that the innovation is specified in great detail, clarifying the intended outcome and the theory of change underpinning the innovation, specifying the relevant implementation strategies and implementing the innovation. If the innovation is implemented exactly as specified, it is then possible to capture outcomes and tie those outcomes to the detail of the innovation and its implementation in a specific context. Implementation outcomes are outcomes that are a direct result of implementation activities or strategies; e.g., is there adequate staffing, are they changing and maintaining behaviours necessary to achieve expected outcomes, and so on. Innovation Outcomes are a direct result of the innovation itself. It is important to consider impact on multiple groups who may benefit from the innovation: e.g., visitors, deliverers and leaders. The involvement throughout of the three groups is noted as crucial. This chimes with research in RCMG where the weak points in projects are often where we have not done enough work to, for example, draw in senior leaders – e.g. Boards of Trustees – and understand their needs, priorities and perceptions as key determinants of success and which would require very specific strategies.

As Laura was one of the authors of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and as this was the framework that first attracted us to Implementation Science, Laura and Caitlin then spent some time walking the Network members through the CFIR and its potential applications. The CFIR is a Framework for implementing an innovation in complex contexts, as described in Figure 1. Identifying and successfully implementing an evidence-based innovation is complex because of the need to adapt and sustain this work in light of a full understanding of the individual (visitors, staff, leaders), inner (the museum) and outer (the broader social realities) contexts; that is, taking research findings and implementing them in the specific context of a particular museum demands a deep understanding of and will be directly affected by the three contextual domains. To aid this work and support the development of methods to embed, sustain and understand the successes and failures of specific evidence-based innovations, the framework sets out the facilitators of and barriers to successful implementation across 5 domains:

- Innovation

- Inner Setting

- Outer Setting

- Individuals Involved

- Implementation Process

The CFIR provides a practical guide to assess and navigate complexity as we work through the implementation pathway. The framework helps us to think through and plan and evaluate implementation in a systematic way. Importantly, it also enables us to identify why an innovation worked. The CFIR embraces complexity but it can also enable us to simplify our approaches enough to help us get to where we need to be.

Working through the complexity

The most challenging and productive aspects of the Workshop involved thinking through some of the complexities that arise from our particular interest in Implementation Science and the specific context of museums. For example, unlike in healthcare, we do not have evidence generated in controlled trials that we want to implement consistently across complex settings. Rather, we have some limited empirical evidence of what works in specific settings and lots of descriptions of ‘best practice’ and theories that hold potential but lack rigour. We can work to map the existing research and identify the most useful ‘evidence’ and most promising best practice (an innovation framework to help us specify the innovation), but the innovations – new exhibitions and inclusive interpretations, particular forms of welcome, inclusive marketing, relationship building, opportunities to engage in particular modes of communication utilised by Visitor Services staff, for example – will remain complex, will be context-specific and difficult to pin down.

Museum evaluations – of which there are many – also don’t help us here. In museums, evaluations of the innovation will often relate to quite limited learning outcomes or be focused even more narrowly on visitor numbers. Key strategic aims to broaden audiences (increasing numbers of museums are making an explicit commitment to broadening their visitor demographics) are rarely measured in any meaningful way and we are unaware of any detailed research which seeks to identify and evaluate the effects of the varied components of the innovation or combinations of components. Indeed, the innovation is rarely specified in full, even once built/developed. Implementation tends not to be identified as a specific and separate discipline. Rather, innovations would tend to be held within project management processes. How, then, could we even begin to utilise Implementation Science and the implementation pathway and process to develop and test implementation methods if we are unclear about what will work?

Here, Laura and Caitlin set out the Hybrid Type 2 design – a route through which we can simultaneously test and refine the innovation and evaluate the implementation. Rather than approaching evidence-based innovation and implementation in a linear way, one at a time, the hybrid approach can save time, lead to the identification of more effective implementation strategies and generate greater overall learning and insight for (museum) leaders (Curran et al 2013).

Based on this, Laura and Caitlin set out a simple 4-stage Implementation Science process:

- Develop the innovation

- Implement the innovation

- Evaluate the implementation

- Evaluate the innovation

This approach raises lots of new questions and begins to define our next steps. In terms of 1. Develop the innovation, we would need clarity on what works, that is, what evidence do we have that specific interventions into museums work to broaden visitor demographics? What theories of change are we basing our work on? What are we setting out to do and who needs to be involved? At Step 2 – Implement the innovation – we would need to utilise the CFIR to identify, across all five domains, the barriers to and facilitators of success and marshal our data in order to develop and specify implementation strategies that are fit for purpose. Once implementation is underway, we would need to work with Implementation Science and Evaluation experts to develop our evaluation methodology for 3. Evaluate the implementation and, linked to this, we would need to build critically on established evaluation techniques in museums and develop new methods to 4. Evaluate the innovation. Prior to all of these steps, we would need to adapt the various tools and frameworks so that they are fit for museums and ensure that we have gleaned any clues about visitation and non-visitation from the population-level data. All of this work will generate data that we will need to analyse and track as we begin to build up our understanding of the outcomes of all this work. It will provide evidence of which innovations and implementation strategies are most effective.

Next steps

Whilst this would mark a significant step change in museums and demands development and testing in situ, it is possible that this approach could draw in the expertise necessary and create the rigour and conditions needed for the co-creation of methods and approaches to enable museums to focus on the attendance gap and gradually generate an accurate understanding of what is required – in terms of innovation and implementation – to close the gap, to sustain representative participation and scale this work up and across the sector.

So, our next phase of research will involve bringing together specific wide-ranging expertise to work out how museums can generate a focus on and become much more systematic and evidence-led in tackling the attendance and benefit gap. Our hypothesis is that we need both a detailed, evidence-based focus on the innovation and a detailed, evidence-based focus on the implementation and that each strand will have different desired outcomes and will demand evaluation. We need to work through this in an active way in the very specific context of a number of museums. However, we think that a focus on and prioritising of the attendance and benefit gap when approached through these processes, could lead to the development of a new area of museum practice and new methods, processes and understanding which could, in turn, lead to a sustained closing of the gap. Our priority now is to work with our museum partners and to convene teams of experts to develop methods and processes equal to this task.

References

Curran G.M., Bauer M., Mittman B., Pyne J.M., Stetler C., ‘Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact’, Med Care, 2012 Mar;50(3):217-26. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e3182408812

Damschroder, L., ‘Clarity out of chaos: Use of theory in implementation research’, Psychiatry Research, 2020-01, Vol.283, p.112461-112461, Article 112461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.036